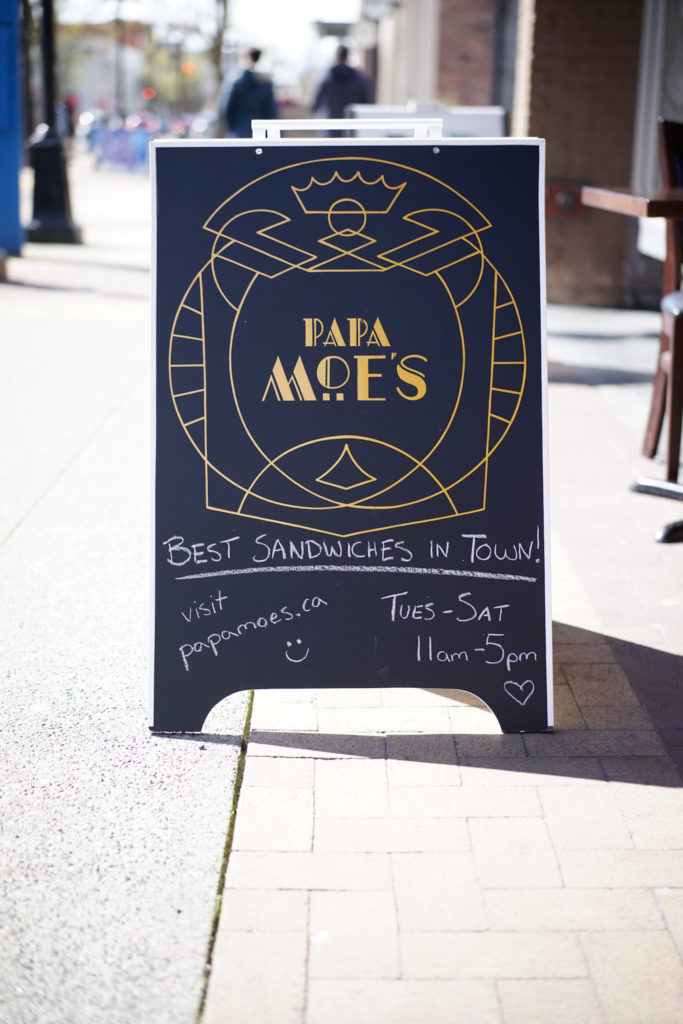

Unorthodox Nosh

A Good Natter About Yiddish Fare with Scott and Seth from Papa Moe’s

A Good Natter About Yiddish Fare with Scott and Seth from Papa Moe’s

What’s the backstory of ‘Papa Moe’, and what led you to try and capture it through your restaurant?

Papa Moe’s is a juxtaposition of both a person–a historical figure who happens to be my grandfather, from New York City–and trying to tie together a certain type of cuisine that isn’t available in Victoria generally. It’s a New York style, Yiddish/Italian-influenced street food.

For context, we were building this restaurant and trying to figure out what kind of food we wanted to do, and we landed on this style of food as an idea. Then the question became, well, how do we want to represent that food? We thought the best way to do it would be through Papa Moe, aka Moses “Moe” Asch.

Papa Moe was the founder of Folkways records–the first independent record label in North America. The Smithsonian actually ended up acquiring his business when he was on his deathbed, so it’s now an American institution.

He was the first person to do liner notes, the first person to do album covers. Many of his artists were marginalized, either through politics or economics. He did a number of field recordings, some of the first field recordings ever done. I would say he was a pioneer of sound, and definitely a pioneer for a certain ‘New York style’.

And he was very proud of his Yiddish roots. His father [Sholem Asch] was a well-known Yiddish writer, and we thought this was a really neat way to celebrate his story, and to bring it to Victoria, packaged together around a unique type of cuisine.

And how have you guys gone about taking those story elements and packaging them into what’s going on at Papa Moe’s now?

One of the big ‘thesis points’ for Folkways records was preservation of culture. A lot of marginalized cultures were producing all sorts of content and artifacts that were not being preserved, or represented sufficiently in mainstream media. Even though we live in a more global culture now, I still think that, in a culinary way, early 20th century New York street food kind of epitomizes that patois of different cultural influences. It’s about coming together, and immigrant communities, and working-class people expressing their culture through food: eating it, sharing it, selling it.

In a lot of ways we think of food as one of the hallmarks, or definitions of, a culture–and in that same sense of what Moe was trying to do with music, we want to make sure that many disenfranchised voices can still be heard.

Could you speak more specifically to the niche you’re targeting in Victoria’s food scene, and how Papa Moe’s fills that gap?

I think the feedback we’ve had since Papa Moe’s launched says a lot. People have really taken to it, they’ve found that the food reminds them of something that they had forgotten, or like a memory that they never knew. Like, what they’d imagined an urban street-food experience to be. It’s really interesting how the food brings out an experience that they just don’t seem to be having in Victoria’s cultural lanscape. It’s something new to them. It’s novel and exciting.

For us personally, I was just craving a Reuben all the time, and I couldn’t find one. One that reminded me of the actual Reubens in New York–so, oh well, I guess we’ll just have to make our own. So it was more a personal, sincere feeling, than saying something like, ‘This is what the city needs.’

Tell me about the Reuben sandwich, and the magic that surrounds it. Is this the iconic sandwich?

The Reuben is iconic. Absolutely. There are other things that we offer that are wonderful, but if someone’s thinking of a New York, Yiddish-inspired grilled sandwich, it’s the Reuben.

But our version is a little different. That’s why we’ve called it ‘The Reubenesque.’ Instead of pastrami, It’s smoked meat. I personally prefer smoked meat over pastrami, and I think the Canadian culture understands it a lot more. And trying to find that rye bread in Victoria was almost impossible. We went through five or six different suppliers, and finally were able to find a local supplier that we really appreciate. They give us a nice dark rye that has that distinctive flavor.

Among the delays we had opening, this was legit one of them: like, fuck, how do we get this rye bread? Because you just can’t do this without rye bread. Victoria, this provincial little town is not quite ready to produce these type of urban tastes. The smoked meat was almost impossible. To try to get smoked meat from Montreal, would be really tough. Many of the big-chain-suppliers are not going to give you a quality product.

So we found that Two Rivers Meats were giving their own meat to another company to smoke. And now we have local–well, pretty darned close–Vancouver-smoked meat, from a high quality butcher, that’s coming to us direct.

So the last part to this one dish, which was also really, really difficult is that we wanted a Russian dressing. But at the moment that we launched, a lot of other things did too. So Russian was no longer the way to go. This was actually a real point of deliberation and reflection: do we call it ‘Sanctioned Sauce’? Do we call it ‘Anti-Freedom Sauce?’ Or do we just call it Russian dressing?

At the end of the day, from the Yiddish perspective, we decided to call it Russian dressing, to make sure that people know what it is–to not try to get cute and clever and political about it. At the end of the day, we’re offering a sandwich. Not a political statement or stance. All the politics we espouse are in the sandwich.

Talk to me about why this style of food–and what you’re doing with it–is interesting.

One of the biggest innovations that I think we’re able to bring to the table, is that we’re not kosher. And this is interesting because we’re a Yiddish inspired space–not trying to be a Jewish deli.

So we can have these dishes with mixtures of ingredients that you’re not ‘supposed’ to put together. Meat and cheese, pork products. Of course we isolate different foods, and make sure that people know exactly what they’re getting. But yeah, we’re probably more kosher in terms of how our vegetarian food interacts with our meat products, than we are in terms of whether meat and cheese go together.

One of the implications of this is that it again speaks to this idea of ‘mixing’–on the culinary level, reflecting a mix on the cultural level, right? It’s not about purity. It’s not exclusive. It’s many groups coming together and making a pastiche, a bricolage, it’s a world of influences coming together.

And in the same way that’s reflected in a lot of aspects of Yiddish culture, it’s also here in the food too. Our food is not Orthodox.

So what does Papa Moe’s future hold? What’s the vision for where you want to take it?

We’ve got the menu that we needed to get open, but it’s pretty bare bones. So definitely more development, playing around with new menu items. And probably then also expand the beverage program. We’ve got local Cherry Cola, which is a classic, and we’re in talks to come up with a Celery Soda, which is a very New York soda, but hard to find. Then eventually we’d like some liquor offerings as well.

But one of the big things about Papa Moe’s is that it’s designed to buttress what we’re doing at [our other joint venture] Cenote. Whereas Cenote is a night place, Papa Moe’s is for the daytime. Cenote is a cocktail lounge, a winter place, a dark, rainy space. Papa Moe’s is bright, airy, warm. We really think that the two of them will work together.

We also think that this is something that lots of places around Victoria would be interested in, let alone the other islands. So we think there will definitely be room for us to grow Papa Moe’s into the future.